The history of tea not only highlights the imperialist origins of the modern consumer, but also provides a context for thinking about the maze of capitalism, politics, and activism

|

| A painting surrounding the tea trade in Guwahati |

Thinking about globalization, we get pictures of Coca-Cola and McDonald's. We can also think of Nike, Apple, Samsung, or numerous other multinational stake-organizations.

We have this right. These multinational corporations literally shape the material experience of countless consumers and workers around the world.

Of course, not all institutions and products get equal global recognition from consumers. Consumer ignorance of their materials, especially in areas such as improving the work environment or environmental pollution, makes it difficult for various political movements to control purchasing power.

Activists are well aware that it is a challenge to inspire consumers to realize the long-term and distant effects of products they buy.

The way we talk about consumers in an inactive or active sense today is a legacy of the cultural and social environment.

It is in this environment that merchants and industrial capitalism have been building since at least the 17th century.

This is the time when the modern concept of the consumer is developed by keeping hands with the development of European imperialism.

The history of tea, in particular, highlights the imperial origins of modern consumers, as well as the background of concern about the maze of capitalism, politics, and activism.

At present tea is produced in about 24 countries including large producing countries like China, India, Sri Lanka, and Kenya.

Advertising and wrap often talk about the 'diverse' source of the drink and long-distance travel. Again, a lot of advertisements have also been circulated to make drinking tea a private, domestic, intensive, feminine, and family form.

The global and internal understanding of this warm drink comes from the global tea trade and the catalytic development of the advertising industry.

It was especially the nations and empires of the 19th and early 20th centuries; closely related to the concept of gender, caste, and class.

The prevailing 19th-century perception of men and women, the people, activism, and inaction has made a place in the fabric of capitalism.

In early modern times, there was no globalization of tea production or cultivation against sugar, cotton, coffee, and tobacco.

The Chinese continued to dominate tea production and exports until they handed over control to the British at the very end of the 19th century.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, noble European and American consumers used to drink tea because of foreign 'diverse' types. Its mysterious source in China adds a different price to this expensive drink.

Tea has also been considered as an Eastern medicine to solve various problems in the West. For example, in a broadside in 1690, herbal trees produced in China and Japan were portrayed as a way to maintain perfect health until old age.

Consumers and poets knew nothing when they spoke about tea or China. But they were well aware of tea's ability to come from China and cure numerous diseases ranging from headaches.

However, as relations between China and the West deteriorated in the 19th century, Europeans began to think of China as a source of various diseases at an increasing rate.

The growing concern about China, the new tea industry founded in British-controlled Assam in the 1830s, was partly the result. It sees success by inciting fear in consumers' minds about Chinese products.

Throughout the 19th century, tea producers and retailers told consumers a variety of stories about the differences between East and South Asia.

British producers have promoted their tea as modern and free from all unhealthy adulteration of tea produced in China as it is produced under the supervision of European managers in India and later in Ceylon.

Consumers have heard special stories about China as well as indirect stories about India, which says that ensuring Europeans oversee product production, wrapping and marketing is a safe way to enjoy global goods. That is, European colonialism makes global products safe and friendly.

|

| Advertisement for tea in 1890 |

More than 70 percent of the exported tea is produced in the empire and about 70 percent is consumed in the empire.

The empire has provided more than three-thirds of the total capital engaged in tea production. All equipment installed in India and Ceylon is of European origin and more than 60% of the boxes used for tea transport are imported from different countries of the empire.

However, when global capitalism collapsed in 1931, this imperial industry collapsed. The tea industry compressed workers and other costs, supported protectionist policies, and reached international agreements to reduce production in 1933. The industry also invests heavily in creating global comprehensive markets.

These ads promote the British consumer empire shopping for the people of Assam and Manchester will ensure job security.

Tea advertisements encourage consumers to buy tea as soon as possible, find tea in stores, encourage friends to drink tea, "create demand for empire tea" and ensure the safety of such teas in the domestic market.

Various types of pictures, shop interiors, exhibitions, and movies promote the tea from British India, Ceylon, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

This kind of global knowledge was important for consumers to avoid foreign alternatives like Chinese tea and make informed decisions.

Within a couple of years, however, the support of big brands, distributors, and consumers has driven producers and advertisers to question whether it is right or not to create a patriotic appeal in the minds of consumers.

In the late 1930s, tea ads made the physical and social pleasures of drinking tea bigger and made the colonial style of the product unimportant.

Such ads have promoted tea as a family drink rather than an imperial product. This approach fits the growing international type of tea production and distribution and coincides with contemporary ideas about advertising lessons by the working class and non-white consumers.

It was also a reaction to verbal protests by workers and nationalist activists busy building negative images of tea gardens.

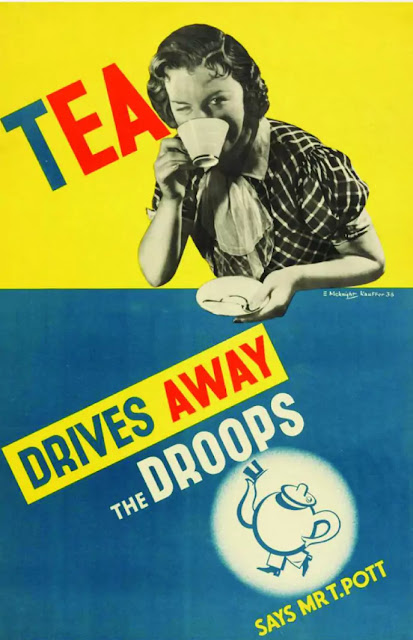

In 1935, British producers established an organization called the International Tea Market Expansion Board to expand the global tea market. Their 'Tea Energizes You' campaign continued till 1952.

The basis of this idea was: Consumers need to be adapted and energized as they are passive, tired, and depressed. Everywhere, this campaign spreads the simple idea that tea stimulates the body, keeps the mind cheerful.

Advertising About tired factory and office workers, housewives and agricultural workers, university students and schoolchildren, all consumers are united.

Newspaper ads, posters, billboards, pamphlets, brochures, films, and radio campaigns have talked about the tea-modern drinks of Britons, Europeans, Americans, Africans, and South and Southeast Asians and it evokes 'fresh' and 'energized' feelings in their work, sports, and homes.

Tea has become a universal path in the modern stressful world. This approach advocates a universal ideal of consumers and products.

|

| An advertisement poster of tea in 1835 |

Consumers have lost their understanding of geographical location, production, and politics even though they have become aware of their bodies and tastes.

Consumers have failed to question where tea came from or how it is being produced in a more important sense from being loyal to the particular product.

From a few generations of conventional advertising, war-time rationing practices, and the development and integration of various large brands, a handful of British consumers in the 1960s are most aware of tea - the idea of being little aware of tea production or imperial history.

A survey conducted by the international advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather in 1965 concluded that 'respondents have a very vague and misleading idea about the production, blending and wrapping of tea.'

Many people know about its arrival from China, India, and Ceylon, but 'most of them don't know where tea comes from, don't know, and don't think it's important.

The history of tea is undoubtedly unique. But the industry's response to the recession refers to the existence of a history of consumer knowledge and ignorance, just like desire and aversion.

This may seem undeniable, but often we consider consumers to be the last point in global processes and historical changes.

Of course, rather than just realizing consumer power, we need to recognize both strong and passive consumers as historical and social elements in the development of the global economy, culture, and political struggle.

If the leaders do not question their perception of what the consumer should know and what should not, the consumer movement will achieve very limited success.

Author: Shawkat Hossain, contributor