|

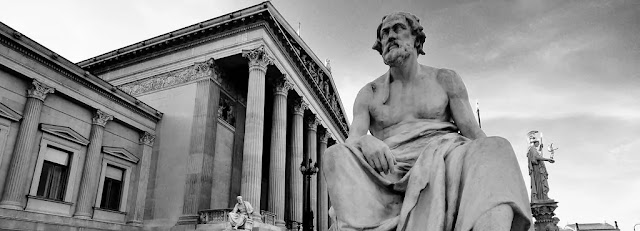

| THUCYDIDES |

Disbelieve it or not, ancient history suggests that atheism is as ancient as the hills

When the American War of Independence began, hereditary monarchs could no longer justify their power as the natural “divine right of kings.”Yet these monarchs still governed the colonists as they had governed England for centuries. In early 1776, Thomas Paine’s pamphlet “Common Sense” convinced the colonists that hereditary monarchy was not a natural form of government.

He pointed out that England had not been united under one king before the Norman Conquest in 1066 and that William the Conqueror used force, not elections, to establish his dynasty.

To Paine—and ultimately to many Americans—the “natural” form of government was democracy, not a hereditary monarchy.

Today, few Americans take monarchy seriously, yet many still think of Christianity as our country’s “natural” belief system.

Even while acknowledging the nation’s religious diversity, Americans often think of their country as a Christian nation, despite the founders being deists, not Christians.

Christianity itself had little influence before 312 C.E. when Emperor Constantine suppressed atheism by using it to establish his own dynasty.

In Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World, Tim Whitmarsh, a professor of Greek culture at Cambridge University, not only demonstrates that “disbelief in the supernatural is as old as the hills,” but also that atheism’s rise in the last two centuries is no historical anomaly.

In fact, “viewed from the longer perspective of ancient history, what is anomalous is the global dominance of monotheistic religions and [their] resultant inability to acknowledge the existence of disbelievers.” Acknowledging atheism’s long history matters, according to Whitmarsh, “not just for intellectual reasons . . . but also on moral, indeed political grounds.

History confers authority and legitimacy . . . If religious belief is treated as deep and ancient and disbelief as recent, then atheism can be dismissed as faddish and inconsequential.”

Understanding atheism’s ancient roots are ultimately “. . . about recognizing atheists as real people deserving of respect, tolerance, and the opportunity to live their lives unmolested.”

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

The Christianization of the Roman Empire put an end to serious philosophical atheism for over a millennium.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

The book introduces more than real people deserving of respect. In this account of history, we are meeting atheism’s founding fathers.

In fascinating detail, Whitmarsh also explains why, from the fourth through eighteenth centuries, atheism seemed to “disappear” from history.

In the fourth century, Roman leaders needed to “hold together a huge, diverse, multi-ethnic, and multilingual territory.”

They used monotheism as their means of consolidation. Atheism thrived in Greece, beginning with the Archaic period (c. 800 B.C.E.) when twelve hundred Greek city-states each had their own cultures and localized religions.

People worshipped the same gods, but these gods had different names in different locations, and religious traditions, rituals, and priests were strictly local.

Because Greece had no political or religious hub, religion had no political power or relevance in that world.

The only role of a priest was to perform sacrifices. Neither omniscient nor omnipotent, the Greek gods themselves were thought to live in this world, usually on distant mountains.

In this socio-political context, atheism became one of many tolerated belief systems and an integral part of the cultural life of Greece.

Atheism emerged with the Pre-Socratics, who “mark the beginning of a journey leading ultimately to what modern atheists call ‘naturalism’: the belief that the physical world is the total sum of reality, that nature rather than divinity structures our existence.”

Fostered by “the absence of state regulation of ideas and (relatedly) the absence of any sense of sacred revelation or sacred text,” the Pre-Socratics conceived ideas that still resonate today.

The philosopher Anaximander, for example, claimed primeval life emerged from the water, and Xenophanes of Colophon foreshadowed “the claims of modern cognitive theorists who explain the origins of religion in terms of a human desire to explain the inexplicable in terms of the intentions of a human-like figure.”

Hippo of Samos equated the soul with the brain, a radical step that made him the first person to have gained the reputation as an atheist.

When Democritus said our universe emerged by chance and was composed only of atoms, he was perhaps the first to ever offer such an explanation.

In the fifth century B.C.E., when Anaxagoras was put on trial for arguing that all life is physical in origin, and for denying the divinity of heavenly bodies, he may have become the first person in history to be prosecuted for heretical beliefs.

From 400-300 B.C.E., atheism progressed further in classical Greece. In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides depicted history as a product of human nature, not divine intervention. Whitmarsh argues that Thucydides’ book “can reasonably be claimed to be the earliest surviving atheist narrative of human history.”

In On the Gods, Protagoras cautioned against believing that non-visible things exist. This book “was almost certainly a discourse attacking the assumption that gods have an objective existence.” Prodicus of Ceos, in On Piety, suggested, as Democritus did, that religion was “the invention of early humanity as it emerged from a state of nature . . . a cultural invention.”

Through his characterization of Sisyphus the mythical son of Aeolus, Critias (a member of Protagoras’ circle) depicted religion as the creation of a “shrewd man who sought to impose order on naïve people” who could then subject citizens’ thoughts to moral scrutiny.

Even Greek theater reflected atheist beliefs. Oedipus Rex “seriously explores the idea of a world without divine determination,” and the characters in the plays of Euripides “deliver sophisticated attacks on traditional religion.”

For example, a line in Bellerophon reads, “Someone says that there really are gods in heaven? There are not, there are not—if you are willing not to subscribe foolishly to the antiquated account.”

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Atheism became one of many tolerated belief systems and part of the cultural life of Greece.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

The play reflects the logic that if gods preside over justice but injustice is not always rectified, then there can be no gods. During the Hellenistic period (338-31 B.C.E.), atheism was fostered by kings like Philip the Great and Alexander III, whose godlike public images eroded the line between the mortal and immortal.

The charismatic skeptic Carneades, head of the Academy founded by Plato, argued that the divine can never be separated from the non-divine, so theism was therefore illogical. In his book On Atheism, Clitomachus built on the ideas of Carneades and “may have invented the idea of atheism as a coherent movement with its own deep history.”

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Neither omniscient nor omnipotent, the Greek gods themselves were thought to live in this world.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

The skeptic Sextus authored 180 dense arguments against the existence of gods. “His catalog. . . is arguably the most important evidence for a sustained, coherent attack on the existence of gods in antiquity.”

Also during this time, the Roman poet Lucretius wrote “On the Nature of Things,” in which Epicurus crusades against oppressive false beliefs about the afterlife to articulate the view that gods have no influence over our lives.

The scholar Stephen Greenblatt credits the poem’s rediscovery in the fifteenth century as the foundation of European secularism and the Renaissance. While atheism was evolving in classical Greece, so was religious orthodoxy.

Athens passed a law allowing public impeachment of those who did not recognize the gods. The name for the crime was asebeia, which means impiety.

Whitmarsh details four prosecutions, including that of Diagoras, “the first person in history to self-identify positively as an atheist.”

He was banished from Athens for writing Arguments that Knock Down Towers, an explicitly atheist tract.

Some of these prosecutions were politically motivated, but in The Laws, Socrates further justified the repression and punishment of atheists by claiming theism to be an essential part of a just society. Atheism’s fortunes further deteriorated after the Punic Wars (246-146 B.C.E.).

Having destroyed Carthage, Rome became a superpower of an interconnected, centralized, and bureaucratized empire.

Religion “provided the most powerful mechanism of symbolic integration.” Stoics encouraged the belief that divine providence had ordained the Roman Empire, and loyal subjects worshipped the emperor.

Under this new political order, however, atheism still existed. In his Natural History, Pliny wrote, “I think of it as a sign of human imbecility to try to find out the shape and form of a god….whoever ‘god’ is—if, in fact, he exists at all.”

He believed gods to be human constructions, born of our desire to elevate ourselves. Atheist writers now had to fear “the boots above their head” and usually wrote books that presented arguments both in favor of, as well as against, believing in the gods.

Whitmarsh thus struggles to tease genuine atheist beliefs out of the literature of the time. The big blow came in 312 C.E. when Constantine defeated Maxentius and re-established the principle of dynastic succession, thus paving the way for Christianity as a state religion.

Political and theological authority became closely interlinked under Constantine, and in 380 C.E., Theodosius I decreed Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman Empire. Anyone not believing in Christ’s divinity was a heretic to be exiled.

This decree completed “the alliance between absolute power and religious absolutism,” and atheism effectively became invisible as “the Christianization of the Roman Empire put an end to serious philosophical atheism for over a millennium.”

Except during the Dark Ages, atheism has flourished throughout history. In Greece, where the clergy did not monopolize learning, atheism was one of many schools of thought dedicated to making sense of the natural world.

Whitmarsh notes that “no war was ever fought for the sake of a god, no empire was expanded in the name of proselytization, no foe was crushed for believing in the wrong god.”

In Rome, however, atheism was pushed underground when monotheism became a tool of the emperor, who claimed for himself the authority of an all-powerful, universal Christian God.

It “was a shrewd exercise in branding for an emperor concerned to hold together a worryingly fissile realm.”

But in the eighteenth century, atheism assumed a new role, and in today’s “advanced capitalist economy based on technological innovation, it has been necessary to claw intellectual and moral authority away from the clergy and reallocate it to the secular specialists in science and engineering.” As the authority and influence of science grow, so will atheism’s.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Roman leaders used monotheism to hold together a huge, diverse, multi-ethnic, and multilingual territory.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

by Mark Kolsen

Mark Kolsen recently retired from teaching high school in Wheaton, Illinois. He is an avid fan of the Four Horsemen, the late Victor Stenger, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali and strives to understand all facets of scientific cosmology and evolutionary biology.

Read next: Coming Out of the Closet as an American Atheist: Why It’s Worth It